Welcome to the final boss of corporate tax strategies. If you’ve made it this far, you know how the game works: it’s legal, it's lopsided, and it favors the entities with in-house counsel and a C-suite full of “performance incentives.”

Now we arrive at the crown jewel of non-cash tax tricks: stock-based compensation. This is the moment where a company can say, with a straight face:

“We just gave our CEO $120 million and somehow reduced our taxable income by even more. Isn’t capitalism efficient?”

Let’s walk through this magnificent piece of legal engineering — and why it’s the final boss in our tax avoidance series.

What Is Stock-Based Compensation?

Stock-based compensation is how companies pay people using equity instead of cash. This includes:

- Stock Options (typically Non-Qualified Stock Options, or NSOs)

- Restricted Stock Units (RSUs)

- Performance Shares

- Stock Appreciation Rights

- Phantom Equity (a very real loophole with a very spooky name)

This approach lets companies:

- Conserve cash

- Boost retention

- “Align incentives” (at least in theory)

- And, importantly: turn non-cash payments into real, cash-equivalent tax deductions

The Mechanics: How the Loophole Works

Step 1: Grant the Stock

A company grants 10,000 stock options to an executive at a strike price of $10.

Step 2: Wait for Vesting and Price Growth

In Year 4, the stock is worth $70.

Step 3: The Executive Exercises the Options

They pay $100,000 (10,000 × $10) to buy stock now worth $700,000. Their taxable gain? $600,000.

Step 4: The Corporation Gets a Deduction

The company gets to deduct $600,000 as a compensation expense — even though it:

- Didn’t spend $600K in cash

- Didn’t give up an asset it previously held

- Already recorded a much smaller expense for book purposes

Result:

- Executive gets rich.

- Company lowers taxable income.

- Book income stays high (since the original expense was amortized and estimated at a much lower value).

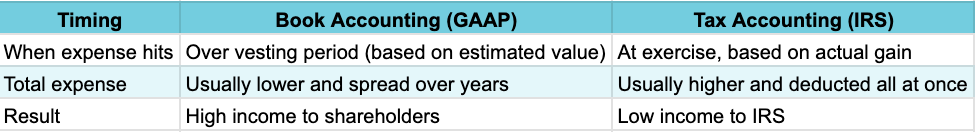

GAAP vs. Tax: The Exploit Is in the Timing

It’s the ultimate arbitrage. You show strength to the markets and weakness to the IRS — in the same breath. And no one calls it cheating because it’s allowed.

Real Examples: Who’s Doing This?

Let’s name names:

Amazon

- Frequently paid employees in RSUs instead of cash

- In 2018: earned $11 billion in U.S. pre-tax income

- Paid $0 in federal taxes

- Why? Among other strategies: $1.1 billion in stock-based comp deductions

Pharma Giants

- Heavily use stock options for senior researchers, execs, and board members

- Large, one-time exercises often wipe out entire tax liabilities

- Example: In 2017, Pfizer deducted $1.3 billion in stock-based comp

Tech Unicorns

- Rely on equity to retain top talent without sacrificing cash flow

- Run unprofitable on paper for years while stock value and tax losses balloon

- Then flip the switch — profitable quarter, massive stock exercises, zero tax

The more successful the company, the bigger the tax deduction.

And the more volatile the stock, the better the timing works in your favor.

What Makes This Absurd?

Let’s review what actually happened:

- No cash changed hands at the time of the deduction

- The company didn’t lose anything in the traditional sense

- They issued stock — which often increases in value because of their own hype

Yet the tax code says:

“Sure, treat it like a $600,000 salary payment. Deduct away.”

Even though:

- It was a stock certificate

- For shares they never purchased

- That were valued years after they were granted

What About Book Income?

Under GAAP (Generally Accepted Accounting Principles):

- Companies expense stock comp gradually, based on grant-date value

- So if the shares were worth $15 each at grant, and they issue 10,000 shares, the total book expense is $150,000

- Even if the market value later balloons to $70/share

This means:

- Book income stays inflated (for investors)

- Taxable income tanks (for the IRS)

- The same compensation is reported at one value to Wall Street and another to the government

And It Gets Better (Worse)

This trick is even more powerful when companies buy back stock to offset dilution. That’s right:

- The company issues shares to execs (tax deductible)

- Then repurchases shares on the open market (non-deductible, but investors like it)

- Result: The appearance of a disciplined, shareholder-friendly company — that just erased its tax bill

Some companies even finance buybacks with debt, creating a second tax deduction from interest.

How Do We Fix This?

Policy ideas on the table:

- Cap corporate deductions at the book expense value (GAAP alignment)

- Disallow deductions for non-cash compensation altogether

- Apply minimum book income tax (which now exists, sort of — thanks to the Inflation Reduction Act)

- Impose clawbacks for stock compensation deductions in cases of executive overpayment or restatements

Will any of these happen?

Possibly. But most corporations would rather fight tooth and nail to protect this — because no tax trick is more profitable, more accepted, or more cleverly hidden in plain sight.

.svg)